- Addressing nutrient pollution through rules and policies in the Bay of Plenty Regional Natural Resources Plan.

- Our Land Management team and Focus Catchments Programme work with landowners to reduce runoff by supporting fencing, planting, nutrient budgeting, and wetland creation.

- Monitor nutrient levels in the harbour and share this data on LAWA

- View the latest nutrient report for Tauranga Harbour.

As Tauranga continues to grow and evolve, so do the pressures on our harbour.

Population growth, land development, and economic activity have all had an effect on Tauranga Harbour. We are working with our communities, iwi and hapū, as well as local industries, to restore and protect it.

Nutrients

Nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus help plants grow—but too much in an estuary can cause eutrophication, leading to poor water quality and excessive sea lettuce (macroalgae) blooms. This impacts the plants and animals that live there. Tauranga Harbour is in a moderate state of health for eutrophication, but nutrient concentrations are at levels that can support excess macroalgae growth.

Nutrients come from fertilizer and livestock run-off from farms, urban and forestry activities, and natural sources like volcanic soils. Over half of the Tauranga Harbour catchment is used for agricultural and horticultural activities.

Sediment

The landscape surrounding Tauranga Harbour has changed a lot in recent decades. Land clearance, farming, logging, mining and urban development have all contributed to increased sediment entering the harbour.

These changes have significantly altered the natural environment, leading to shallower navigation channels, and the loss of important habitats such as seagrass beds, juvenile fish nurseries, and shellfish areas. While modern land-use controls are now in place, the harbour continues to feel the effects of past land modifications, with ongoing sedimentation still impacting its ecological health.

- We’ve set clear rules and policies through the Bay of Plenty Regional Natural Resources Plan to help manage sediment entering our waterways and harbour.

- Our Land Management team and Focus Catchments Programme work closely with landowners to reduce sediment runoff—this includes retiring and planting steep or erosion-prone land, and creating riparian buffers or wetlands.

- We support proven solutions like building detainment bunds and detention dams to trap sediment before it reaches streams and rivers.

- We monitor sediment levels and mud content across the harbour and share this data on LAWA Estuaries.

- Check out the latest sedimentation report for Tauranga Harbour.

Mangroves

There are 70 species of Mangrove found around the world. In New Zealand, only one species is present, Avicennia marina Subspecies Australasica or Manawa. This remarkable species has been part of New Zealand’s coastal ecosystems for approximately 19 million years and is the southernmost mangrove species found anywhere on Earth.

Mangroves play an important role in the ecology of the Tauranga Harbour. They help stabilise shorelines by reducing coastal erosion and act as a natural buffer against storm surges. They also create essential habitats for a wide range of native species. Manawa provide a nursery environment for juvenile fish such as short-finned eel and yellow-eyed mullet, and support populations of native insects, birds, crabs, shellfish, snails, and algae.

Changes in land use across the Tauranga Harbour catchment — including subdivision development and bush clearance — have increased the amount of sediment and nutrients flowing into the harbour. This has led to a significant expansion of mangrove coverage, particularly across open tidal flats and in sub-estuaries like Te Puna, Waikareao, and Waimapu.

Council is working with landowners and industry to reduce sedimentation which exacerbates mangrove spread. We also support estuary care groups in their restoration work. See how you can get involved here: Estuary Care groups As a volunteer, if you would like to manage mangroves in your area, visit Managing mangroves to see what activity is permitted in your area.

Saltmarsh

Saltmarsh is a vital part of our estuarine environment, forming the fringing margin between land and sea. Locally, common saltmarsh species include oioi, sea rush, and saltmarsh ribbonwood.

These habitats are highly productive ecosystems that trap and filter sediment and nutrients, helping to improve water quality. They also act as a natural buffer, protecting against invasive grasses and weeds, and provide essential habitat for a wide range of native fish and bird species.

Saltmarsh delivers a variety of ecosystem services — including flood protection, erosion control, and carbon storage as part of the blue carbon cycle. Beyond their ecological role, saltmarsh and wetland areas hold deep cultural and spiritual significance for Māori. They are valued as traditional sites for gathering food and rongoā (medicines), and as habitats for many taonga species, including fish, birds, and plants used for weaving.

Across the Bay of Plenty, saltmarsh habitats have experienced significant loss, particularly due to land reclamation. In Tauranga Harbour alone, approximately 693 hectares of saltmarsh have been lost. These important ecosystems continue to face ongoing threats, including rising sea levels, declining water quality, trampling by livestock, and the spread of invasive species.

Council has been undertaking a range of saltmarsh restoration and enhancement projects in recent years, including the re-wetting of previously drained land to restore saltmarsh. We support landowners to undertake environmental programmes on their properties to provide biodiversity and water quality benefits, supported by the Environmental Programme Grants Policy.

We have undertaken research to investigate suitable site locations for saltmarsh restoration, and partnered with various organisations to undertake blue carbon measurements, to track how effective our local saltmarsh is at storing blue carbon. We also have an estuarine wetland monitoring network, which includes the use of Surface Elevation Tables to see whether saltmarsh will keep pace with rising sea levels.

Seagrass

Seagrass is a flowering plant that thrives in shallow, coastal areas like estuaries. Seagrass helps clean the water, stores carbon and provides homes for thousands of species. It can be an excellent indicator of environmental change and impact.

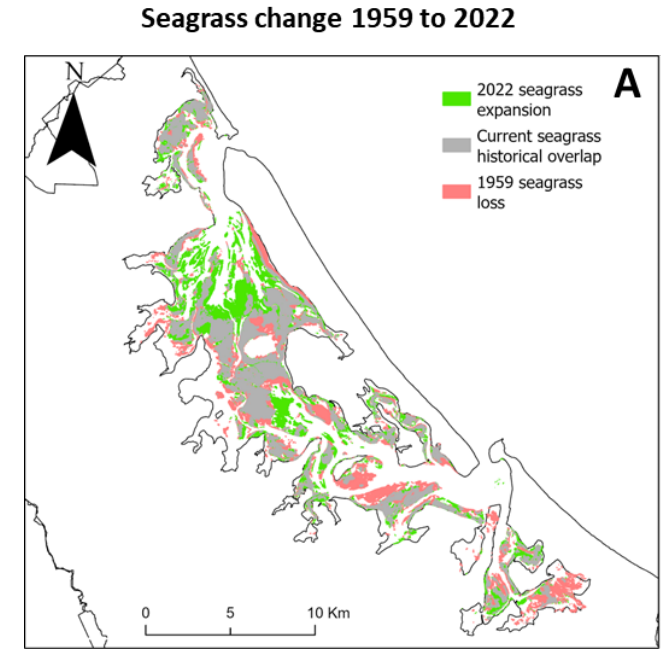

Across the world, seagrass beds are declining. In Tauranga Harbour, seagrass cover experienced a significant historical loss of around 66% between 1959 and 1996, followed by a further 4% decline through to 2011. However, by 2022, encouraging signs of recovery have emerged. Seagrass extent in both the northern and southern parts of the harbour has returned to levels similar to those seen in 1996.

More info about seagrass recovery

This recovery includes subtidal seagrass, which remains permanently underwater — a promising sign that water clarity and sediment conditions have improved enough to support regrowth. These improvements align with our river water quality data, which shows positive trends in reduced sediment and nutrient levels at many sites around the harbour.

Areas near the harbour entrance with little land runoff or influence from other catchments have shown the smallest decline in seagrass abundance.

Change in seagrass extent in Tauranga Harbour. Green = most recent expansion, grey = 2022 seagrass overlap with 1959, and red = areas of seagrass lost from 1959 to 2022.

Change in seagrass extent in Tauranga Harbour. Green = most recent expansion, grey = 2022 seagrass overlap with 1959, and red = areas of seagrass lost from 1959 to 2022.

A variety of stressors impact on seagrass, including sedimentation and reduced light availability, nutrient enrichment, marine heatwaves, physical disturbance (e.g. loss from reclamation, dredging, anchoring and moorings), waterfowl grazing and disease.

Sea lettuce

Sea lettuce (Ulva spp) is a naturally occurring green algae (seaweed) native to New Zealand. Under the right conditions it can develop large problematic blooms, which have been reported anecdotally back as early as the 1940s.

Tauranga Harbour, with its shallow flats and channels, has plenty of nutrients and good water clarity for photosynthesis; perfect for sea lettuce growing conditions. When sea lettuce 'blooms' it affects the way the harbour looks, and how we use it. Sea lettuce gets ripped off the sea-bed by strong on-shore winds or heavy seas. It can drift around the harbour and nearshore coastal waters and interfere with fishing nets and lines and boat propellers.

It keeps growing as it floats around and then gets washed up on the beaches with on-shore winds. Decayed sea lettuce produces an offensive sulphur odour. When washed up piles of sea lettuce decompose on the beaches or in shallow areas, more nutrients are released into the harbour system and sea lettuce growth is promoted.

Sea lettuce varies in abundance from year to year and place to place, but sea lettuce blooms have reduced significantly since the early 90s thanks to work on reducing larger nutrient inputs to the harbour. Smaller blooms are driven by nitrogen inputs from rivers, groundwater and oceanic upwelling, when temperatures and climatic conditions are suitable.

We are responding to community concerns about sea lettuce in three ways:

- Reducing the amount of nutrients entering Tauranga Harbour by working with land owners, business owners, local councils and the wider community to:

-

-

Reduce diffuse nutrient sources such as from agricultural runoff and nutrients that drain through the soil and into groundwater which eventually enters the harbour.

-

-

-

Prevent point sources of nutrients such as from septic tank seepage and storm water drains.

-

-

Investing in monitoring to continue to understand the relationships between nutrients and sea lettuce (and other algae) growth.

-

Reducing the public nuisance factor and hydrogen sulphide risk in the most severe sea lettuce bloom years by working with Tauranga City and Western Bay of Plenty District Councils to remove sea lettuce from high use public areas around the Tauranga Harbour (where feasible and affordable).

Wherever possible, the sea lettuce is dewatered and taken for composting along with other green waste. In the rare instances that the collected sea lettuce is too badly decomposed, contaminated with sand or there’s too much of it for the compost facility to handle, it may be disposed of to landfill.

What you can do

You can help manage sea lettuce by collecting it from the foreshore and using it as a fertiliser or compost supplement in your garden. Wash it and use it sparingly to avoid salt build-up in your soil. Find out more in this Sea Lettuce and the Garden booklet, produced by Tauranga HarbourWatch Inc.

Other nuisance macroalgae species

There are other species of algae that can create blooms in Tauranga Harbour, and in recent years we have seen a rise in the abundance of a variety of filamentous algae blooms.

These tend to begin growing on the intertidal sandflats on top of seagrass beds, and can create nuisance quantities of algae, which can interfere with fishing and boating activities. These can also create a smell and mess when they get pushed into the high shore and break down.

The blooms are likely driven by warm water conditions and excess nutrients, however we need to continue to invest in research to understand how we might manage these in the future.

Green and red filamentous algae.